“We’re going to be talking about consent? (giggles). You mean sex? (giggles).”

When students say that, I respond with “consent is not just about sex. That’s just one part of it.”

When adults question me, I say something like “consent is not just a one-time conversation about sex. It is a transferable skill that requires practice, introspection, and application throughout our whole span of human interaction. It also requires us (adults) to model how to ask for and how to respect consent.”

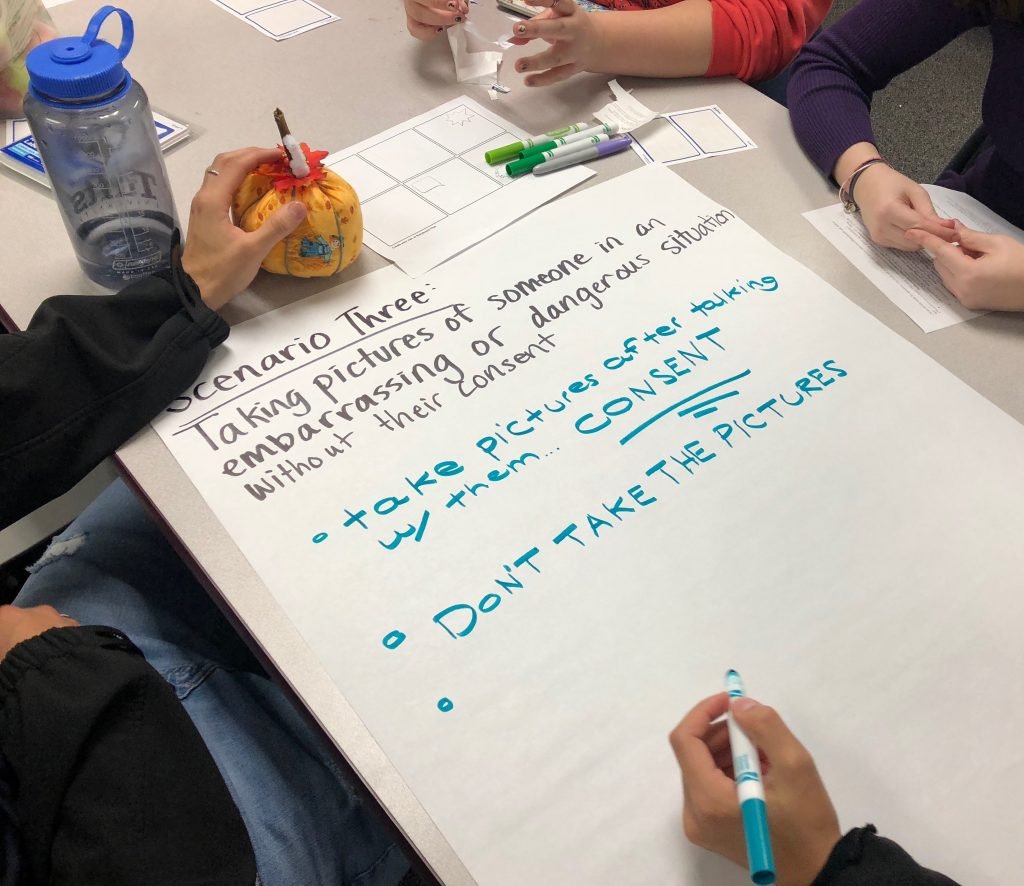

In the classroom, we stress that consent is fundamental to healthy relationships- and that it means many things. To teach about consent, we often do an interactive activity where students model consent. Then, we ask questions that examine not just what consent is, but who we need to establish consent with, when we should ask for consent, and HOW to get consent. Let’s break those questions down.

Question one: What is consent?

The most common student responses to this question are permission and agreement. But what do these words mean? What are the feelings and associations these words evoke? As I say to the students, “how does how we think about consent impact the way we enact consent in our lives?”

There is a distinction between “permission” and “agreement.” Permission implies a one-sided exchange. It is a simple yes or no. It’s one person asking someone else if they allow a particular thing to happen (sometimes students say the word “allowance” too). Consent as permission is often the version of consent that teens use with adults or authority figures (someone who holds power). In these conversations, consent may sound like: “can I borrow the car? Can I leave class and go to the bathroom? Can I hang out with this friend after school? Can I eat the leftovers? Yes or no?”

Consent as an agreement feels different. An agreement is a mutual exchange. It’s two or more people checking in and seeing if it works for everyone. Do we want this? Is this ok for us? Agreement implies consensus, discussion, and a mutual desire for a specific thing.

Question two: Who do we need to get consent with?

But who are we doing this with? I typically work first to dispel the myth that when we talk about consent, we are only talking about sex with romantic partners. Yes, consent conversations include topics like sex and physical intimacy, but they also include posting pictures, hanging out with a friend, sharing secrets, giving hugs, and so much more. Consent is about empathetic, everyday human interaction, whether that occurs in a physical, digital, or emotional space.

To answer the question: we need to get consent with everyone.

This could look like:

- To a colleague: “May I borrow your stapler?”

- To a romantic partner: “is it ok if I sit close to you, or do you want some space to decompress after work?”

- To a family member: “can I post this picture of your cute new baby, or do you prefer to keep those images private?”

- To a friend: “what do you want to do when we hang out?”

- To a stranger: noticing that they moved away from you, and stepping back to give them room

Question three: When do we need to get consent?

All the time. Consent is an ongoing process, not a one-time ask. Ongoing means throughout a relationship and during an interaction. Maybe my partner and I both consented to something but then my partner doesn’t consent any more. They have that right and I have the responsibility to respect and honor that- and to do so without making them feel bad, guilty, or less than for not wanting to continue. Some complain that stopping is hard, or not fair, or confusing, but respecting someone’s wishes is what true consent looks like. It’s checking in over and over and over again to make sure everyone is still enthusiastic about whatever it is we’re doing, saying, experiencing, or sharing together.

Question four: How do we ask for or get consent?

So if we’re checking in all the time, how do we do that? To me, that’s the essential question. Not just what is consent, but how do we get it? What is the skill of asking for consent? What does it actually look like in our lives?

Many students answer that the way to get consent is to ask or communicate. “Yes!” I say, “but what do you mean? What specific questions could you ask?” This typically causes another wave of giggles, regardless of what grade I’m in, which I (attempt to) alleviate by saying “you don’t have to say what you’d be asking for- just how you would ask. Let’s say the frame of a question and fill in the blank.” Students then come up with questions like: can I…? is it ok if…? Do you want to…? (and on and on).

Sometimes it’s awkward and sometimes they struggle to generate questions. But that’s why it’s so important to practice consent at school and at home. Now they’ve already said the words. Thinking about what questions we’d ask someone to get consent forces us to practice using language and navigate these conversations in advance. That way, when we’re in the moment we don’t think “shoot, now I have to get consent… how do I do that?” Instead, we’ll remember to ask “what do you want to do? Is this ok? Do you like this?”

It is important to teach that consent isn’t just about asking. Learning about consent also requires that we develop our skills around self-regulation and respecting someone’s wishes when they don’t consent to something we want to do. That part of consent can feel tricky, but it’s crucial. Wanting to do something and consenting to it doesn’t give me the right to do it- and doesn’t mean the other person consents. If we don’t agree, or they don’t want (whatever it is), it’s not mutual and it’s not consent.

Part of our conversations about consent involve reflecting on our power and privilege when asking for consent. How could my identity impact someone’s ability to consent? What power differentials exist? How does my identity make that person feel? Can consent be freely given or does my power make that impossible – or even complicated?

The most important thing to remember about consent is that it is more than just a yes or no.

Consent is a mutual agreement. Consent is an agreement that requires buy in from both sides, in an equitable relationship, and requires a big dose of empathy.

Thinking about consent as a form of empathy reinforces the importance of consent as a transferable skill. It makes us ask ourselves: am I treating people with empathy? How am I checking in to see if this is ok? How can I be a better partner, friend, family member, classmate, teammate, or coworker in order to help another person feel wholly validated, valued, and respected as an individual?

Consent may seem like a lot, but checking in can take a fraction of a second and models respect and empathy. Although we often don’t believe it, the young people in our lives look to us as examples, and modeling consent- the complexity, nuance, and simplicity of it- helps young people (our future) experience the respect, empathy, and consent that we all deserve. Our goal then is to ask, model, and teach these skills so that this future becomes their reality.