“You shouldn’t have been wearing high heels!”

– Mother to daughter who was assaulted on her way home from work

“Truthfully, I was a very sexual girl. I really don’t think he was at fault because I was just so promiscuous, he couldn’t help it.”

– Adult survivor, describing sexual abuse she experienced as a five-year-old child

“I’m so sorry you had to come out in the middle of the night. I never should’ve left my house; this is all my fault.”

– Survivor to her medical advocate at a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) exam, hours after she was raped by a stranger at gunpoint.

“Is what he did to me… does it make me less of a man? Is there something about me that made him think I wanted this?”

– Male survivor, describing sexual abuse by his step-father

Seventeen years ago this October, I shared my story of surviving sexual assault publicly for the very first time. I did this not to seek revenge or draw attention to my experience, but because I knew that there were others. I knew that there would be people in the audience who heard my story and had experiences like mine and who were suffering in silence. I hoped that sharing my story might prevent someone else from getting hurt. I spoke that day because I knew how much it would have meant to me to hear another survivor and know that I was not alone. While I knew that there would be survivors in the room, the response I received still overwhelmed me. Dozens of survivors came forward, many of whom had never before told anyone.

Since that day, I have been in many spaces where I have had the honor of hearing stories from survivors of gender-based violence. From the crowds at Take Back the Night events, to medical exam rooms where I acted as a sexual assault medical advocate, to training employers in conference rooms- my job is to bring topics that are so often shrouded in secrecy and shame into the light so that survivors know that help and support is available, and abusers know that they will be held accountable. My first speech all those years ago was entitled “Breaking the Silence.” It’s what I still do at REACH, every day.

Since that day, I have been in many spaces where I have had the honor of hearing stories from survivors of gender-based violence. From the crowds at Take Back the Night events, to medical exam rooms where I acted as a sexual assault medical advocate, to training employers in conference rooms- my job is to bring topics that are so often shrouded in secrecy and shame into the light so that survivors know that help and support is available, and abusers know that they will be held accountable. My first speech all those years ago was entitled “Breaking the Silence.” It’s what I still do at REACH, every day.

Over the past couple of weeks, I have witnessed, as many of us have, hundreds of survivors breaking their silence. I’m watching on TV, I’m seeing it in the paper, it’s my entire social media feed. Story upon story of pain, trauma, resilience, healing. Domestic and sexual violence, issues that for so long have been considered taboo and private, are now dominating the public discourse. Hearing these stories can be inspiring, triggering, overwhelming. One of the themes I have heard in many of these stories, both recently and throughout the years, is blame. Blame is a reaction that can be hard to hear, and it’s one that I think needs to be examined.

The reality and the prevalence of sexual and domestic violence is staggering. This came to light for many on October 15th, 2017. Actor Alyssa Milano used the hashtag #metoo, a movement founded by Tarana Burke, and asked that anybody who had been sexually harassed or assaulted to retweet #metoo to help illustrate the scope and prevalence. In the first 24 hours, half a million people responded to her initial tweet on Twitter; there were 12 million posts and comments in response to her post on Facebook, and 45% of Facebook users reported knowing someone who posted #metoo. Suddenly, something that many of us wanted to think of as rare, isolated incidents was thrust into sharp focus. The #metoo movement made us face into the reality that sexual assault and relationship violence had happened to people we know and love. Often the people we may never have guessed had experienced this form of trauma. And suddenly an uncomfortable thought crept into the consciousness of many- ‘if it could happen to them, could it happen to me?’

To me, the underbelly of blame is fear. It’s scary and overwhelming to think that domestic and sexual violence can happen to anyone, and has happened to so many. Blame is a way to try to make ourselves feel safer. We tell ourselves that it is the victim’s fault and that they must have done something to bring upon their own victimization, so that we can believe that we would know better and do better and therefore avoid the same pain. As Gavin de Becker says in his book, “The Gift of Fear,” this denial is a save now, pay later scheme.

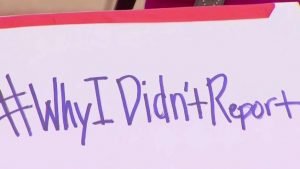

Many of the survivors who have come forward over the past week using the hashtag #whyididntreport share experiences of telling a friend or family member and not being believed or being blamed for their assault. When a survivor goes to someone they trust and discloses a trauma and are met with blame and disbelief it can actually feel worse than the initial trauma itself. And for many, it makes it difficult to ever think about telling someone else. As I once heard a civil attorney say, “The damage that is done is less about the event or violence itself. The suffering a survivor experiences is more about how long the secret has been held.”

Even if we don’t overtly blame a survivor when we are face to face with them, the comments we make about stories in the news can sound a powerful message to the folks around us- who may or may not be survivors themselves. For instance, if we make a comment to a colleague or at a family event that if what happened to Christine Blasey Ford was really “that bad,” then she would have reported it right away, a person who overhears this comment may feel shame that they didn’t report their own assault or confusion about why something that others don’t think is a big deal has had such a profound impact on their life.

I did not report my assault. I never even considered it. Even as a teenager, I knew that the legal system was not set up to support me, and would more likely retraumatize me by further taking control away after my control was taken during my assault. Several years ago, while being interviewed on a cable access show for Sexual Assault Awareness Month, the host grew very angry with me for not reporting. “What is to stop him from doing it again?” She fired at me. “Wouldn’t you blame yourself if you learned there were other victims?”

Blame myself? Sure. I had lots of experience with that. Self-blame is a reaction that many survivors are familiar with. If we believe that we were not at fault for our assault, it can feel overwhelming- it can make us feel more vulnerable. Self-blame can be a strategy to make us feel more in control and able to protect ourselves from further harm in the future. So we may tell ourselves, “It happened because I was drunk. I’ll just never drink again and I will be safe.”

One survivor I worked with convinced herself that she was abused by a relative because of her appearance. So in order to feel in control and safe, she gained over 100 pounds in a year. Abuse and assault don’t happen because someone is drinking or because of the shape of someone’s body. They happen because someone makes the choice to hurt someone else. Blame, whether internalized or verbalized by others, keeps survivors suffering in silence. It allows these issues to remain unspoken and unaddressed. It makes it easier for us to look the other way when someone we know is acting controlling or ignores someone’s boundaries. We place the responsibility of sexual and domestic violence squarely on the shoulders of those who have experienced it.

It is overwhelming to face the reality of sexual and domestic violence. Survivors are demanding we do so now. In 2014, almost exactly 4 years ago, I wrote a blog entitled, “What will it take for us to believe survivors?” I’m asking this question again. It may feel easier to blame victims and minimize their experiences, but it puts everyone in more danger. It allows abusers to remain unchecked and continue their sense of entitlement. It further isolates and shames survivors, making it difficult for many to receive the support and help they deserve.

At REACH, we believe that change is possible. Change becomes possible when instead of blaming and shaming survivors, we listen and believe. Rather than hold survivors responsible for their own victimization, we can hold abusers accountable for their behavior. Instead of blaming survivors for not reporting their abuse to authorities, we can work to change the institutions, laws, and practices that make reporting feel impossible for so many. When we #believesurvivors we can shift attitudes, beliefs, and social norms. We can change and transform systems. We can interrupt cycles of violence and eradicate it all together. We can reach beyond domestic violence.